- ASIC

- Battery management ICs

- Clocks and timing solutions

- ESD and surge protection devices

- Automotive Ethernet

- Evaluation Boards

- High reliability

- Isolation

- Memories

- Microcontroller

- Power

- RF

- Security and smart card solutions

- Sensor technology

- Small signal transistors and diodes

- Transceivers

- Universal Serial Bus (USB)

- Wireless connectivity

- Search Tools

- Technology

- Packages

- Product Information

- Ordering

- Overview

- Automotive Ethernet Bridges

- Automotive Ethernet PHY for in-vehicle networking

- Automotive Ethernet Switches for in-vehicle networking

- Overview

- Defense

- High-reliability custom services

- NewSpace

- Space

- Overview

- Embedded flash IP solutions

- Flash+RAM MCP solutions

- F-RAM (Ferroelectric RAM)

- NOR flash

- nvSRAM (non-volatile SRAM)

- PSRAM (Pseudostatic RAM)

- Radiation hardened and high-reliability memories

- SRAM (static RAM)

- Wafer and die memory solutions

- Overview

- 32-bit FM Arm® Cortex® Microcontroller

- 32-bit AURIX™ TriCore™ microcontroller

- 32-bit PSOC™ Arm® Cortex® microcontroller

- 32-bit TRAVEO™ T2G Arm® Cortex® microcontroller

- 32-bit XMC™ industrial microcontroller Arm® Cortex®-M

- Legacy microcontroller

- Motor control SoCs/SiPs

- Sensing controllers

- Overview

- AC-DC power conversion

- Automotive conventional powertrain ICs

- Class D audio amplifier ICs

- Contactless power and sensing ICs

- DC-DC converters

- Diodes and thyristors (Si/SiC)

- Gallium nitride (GaN)

- Gate driver ICs

- IGBTs – Insulated gate bipolar transistors

- Intelligent power modules (IPM)

- LED driver ICs

- Motor drivers

- MOSFETs

- Power modules

- Power supply ICs

- Protection and monitoring ICs

- Silicon carbide (SiC)

- Smart power switches

- Solid state relays

- Wireless charging ICs

- Overview

- Antenna cross switches

- Antenna tuners

- Bias and control

- Coupler

- Driver amplifiers

- Rad hard microwave and RF

- Low noise amplifiers (LNAs)

- RF diode

- RF switches

- RF transistors

- Wireless control receiver

- Overview

- Calypso® products

- CIPURSE™ products

- Contactless memories

- OPTIGA™ embedded security solutions

- SECORA™ security solutions

- Security controllers

- Smart card modules

- Smart solutions for government ID

- Overview

- ToF 3D image sensors

- Current sensors

- Gas sensors

- Inductive position sensors

- MEMS microphones

- Pressure sensors

- Radar sensors

- Magnetic position sensors

- Magnetic speed sensors

- Overview

- Bipolar transistors

- Diodes

- Small signal/small power MOSFET

- Overview

- Automotive transceivers

- Control communication

- Powerline communications

- Overview

- USB 2.0 peripheral controllers

- USB 3.2 peripheral controllers

- USB hub controllers

- USB PD high-voltage microcontrollers

- USB-C AC-DC and DC-DC charging solutions

- USB-C charging port controllers

- USB-C Power Delivery controllers

- Overview

- AIROC™ Automotive wireless

- AIROC™ Bluetooth® and multiprotocol

- AIROC™ connected MCU

- AIROC™ Wi-Fi + Bluetooth® combos

- Overview

- Commercial off-the-shelf (COTs) memory portfolio

- Defense memory portfolio

- High-reliability power conversion and management

- Overview

- Rad hard microwave and RF

- Radiation hardened power

- Space memory portfolio

- Overview

- Parallel NOR flash

- SEMPER™ NOR flash family

- SEMPER™ X1 LPDDR flash

- Serial NOR flash

- Overview

- FM0+ 32-bit Arm® Cortex®-M0+ microcontroller (MCU) families

-

FM3 32-bit Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU) families

- Overview

- FM3 CY9AFx1xK series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9AFx1xL/M/N series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9AFx2xK/L series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9AFx3xK/L series ultra-low leak Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9AFx4xL/M/N series low power Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9AFx5xM/N/R series low power Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9AFxAxL/M/N series ultra-low leak Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9BFx1xN/R high-performance series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9BFx1xS/T high-performance series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9BFx2xJ series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9BFx2xK/L/M series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

- FM3 CY9BFx2xS/T series Arm® Cortex®-M3 microcontroller (MCU)

-

FM4 32-bit Arm® Cortex®-M4 microcontroller (MCU) families

- Overview

- FM4 CY9BFx6xK/L high-performance series Arm® Cortex®-M4F microcontroller (MCU)

- FM4 CY9BFx6xM/N/R high-performance series Arm® Cortex®-M4F microcontroller (MCU)

- FM4 S6E2C high-performance series Arm® Cortex®-M4F microcontroller (MCU)

- FM4 S6E2G series connectivity Arm® Cortex®-M4F microcontroller (MCU)

- FM4 S6E2H high-performance series Arm® Cortex®-M4F microcontroller (MCU)

- Overview

-

32-bit TriCore™ AURIX™ – TC2x

- Overview

- AURIX™ family – TC21xL

- AURIX™ family – TC21xSC (wireless charging)

- AURIX™ family – TC22xL

- AURIX™ family – TC23xL

- AURIX™ family – TC23xLA (ADAS)

- AURIX™ family – TC23xLX

- AURIX™ family – TC264DA (ADAS)

- AURIX™ family – TC26xD

- AURIX™ family – TC27xT

- AURIX™ family – TC297TA (ADAS)

- AURIX™ family – TC29xT

- AURIX™ family – TC29xTT (ADAS)

- AURIX™ family – TC29xTX

- AURIX™ TC2x emulation devices

-

32-bit TriCore™ AURIX™ – TC3x

- Overview

- AURIX™ family - TC32xLP

- AURIX™ family – TC33xDA

- AURIX™ family - TC33xLP

- AURIX™ family – TC35xTA (ADAS)

- AURIX™ family – TC36xDP

- AURIX™ family – TC37xTP

- AURIX™ family – TC37xTX

- AURIX™ family – TC38xQP

- AURIX™ family – TC39xXA (ADAS)

- AURIX™ family – TC39xXX

- AURIX™ family – TC3Ex

- AURIX™ TC37xTE (emulation devices)

- AURIX™ TC39xXE (emulation devices)

- 32-bit TriCore™ AURIX™ – TC4x

- Overview

- PSOC™ 4 Arm® Cortex®-M0/M0+

- PSOC™ 4 HV Arm® Cortex®-M0+

- PSOC™ 5 LP Arm® Cortex®-M3

- PSOC™ 6 Arm® Cortex®-M4/M0+

- PSOC™ Multitouch Touchscreen Controller

- PSOC™ Control C3 Arm® Cortex®-M33

- PSOC™ Automotive 4: Arm® Cortex®-M0/M0+

- PSOC™ Edge Arm® Cortex® M55/M33

- Overview

- 32-bit TRAVEO™ T2G Arm® Cortex® for body

- 32-bit TRAVEO™ T2G Arm® Cortex® for cluster

- Overview

- 32-bit XMC1000 industrial microcontroller Arm® Cortex®-M0

- 32-bit XMC4000 industrial microcontroller Arm® Cortex®-M4

- XMC5000 Industrial Microcontroller Arm® Cortex®-M4F

- 32-bit XMC7000 Industrial Microcontroller Arm® Cortex®-M7

- Overview

- Legacy 32-bit MCU

- Legacy 8-bit/16-bit microcontroller

- Other legacy MCUs

- Overview

- AC-DC integrated power stage - CoolSET™

- AC-DC PWM-PFC controller

- Overview

- Bridge rectifiers & AC switches

- CoolSiC™ Schottky diodes

- Diode bare dies

- Silicon diodes

- Thyristor / Diode Power Modules

- Thyristor soft starter modules

- Thyristor/diode discs

- Overview

- Automotive gate driver ICs

- Isolated Gate Driver ICs

- Gate driver ICs for GaN HEMTs

- Level-Shift Gate Driver ICs

- Low-Side Drivers

- Transformer Driver ICs

- Overview

- AC-DC LED driver ICs

- Ballast IC

- DC-DC LED driver IC

- LED dimming interface IC

- Linear LED driver IC

- LITIX™ - Automotive LED Driver IC

- NFC wireless configuration IC with PWM output

- VCSEL driver

- Overview

- PSOC™ Control C3 Arm® Cortex®-M33

- Motor control SoCs/SiPs

- BLDC motor drivers

- BDC motor drivers

- Stepper & servo motor drivers

- Motor drivers with MCU

- Bridge drivers with MOSFETs

- Gate driver ICs

- Overview

- Automotive MOSFET

- Dual MOSFETs

- MOSFET (Si & SiC) Modules

- N-channel depletion mode MOSFET

- N-channel MOSFETs

- P-channel MOSFETs

- Silicon carbide CoolSiC™ MOSFETs

- Small signal/small power MOSFET

- Overview

- Automotive transceivers

- Linear Voltage Regulators for Automotive Applications

- OPTIREG™ PMIC

- OPTIREG™ switcher

- OPTIREG™ System Basis Chips (SBC)

- Overview

- eFuse

-

High-side switches

- Overview

- Classic PROFET™ 12V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- Classic PROFET™ 24V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- Power PROFET™ + 12/24/48V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- PROFET™ + 12V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- PROFET™ + 24V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- PROFET™ + 48V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- PROFET™ +2 12V | Automotive smart high-side switch

- PROFET™ Industrial | Smart high-side switch

- PROFET™ Wire Guard 12V | Automotive eFuse

- Low-side switches

- Multichannel SPI Switches & Controller

- Overview

- Radar sensors for automotive

- Radar sensors for IoT

- Overview

- EZ-USB™ CX3 MIPI CSI2 to USB 3.0 camera controller

- EZ-USB™ FX10 & FX5N USB 10Gbps peripheral controller

- EZ-USB™ FX20 USB 20 Gbps peripheral controller

- EZ-USB™ FX3 USB 5 Gbps peripheral controller

- EZ-USB™ FX3S USB 5 Gbps peripheral controller with storage interface

- EZ-USB™ FX5 USB 5 Gbps peripheral controller

- EZ-USB™ SD3 USB 5 Gbps storage controller

- EZ-USB™ SX3 FIFO to USB 5 Gbps peripheral controller

- Overview

- EZ-PD™ CCG3 USB type-C port controller PD

- EZ-PD™ CCG3PA USB-C and PD

- EZ-PD™ CCG3PA-NFET USB-C PD controller

- EZ-PD™ CCG7x consumer USB-C Power Delivery & DC-DC controller

- EZ-PD™ PAG1: power adapter generation 1

- EZ-PD™ PAG2: Power Adapter Generation 2

- EZ-PD™ PAG2-PD USB-C PD Controller

- Overview

- EZ-PD™ ACG1F one-port USB-C controller

- EZ-PD™ CCG2 USB Type-C port controller

- EZ-PD™ CCG3PA Automotive USB-C and Power Delivery controller

- EZ-PD™ CCG4 two-port USB-C and PD

- EZ-PD™ CCG5 dual-port and CCG5C single-port USB-C PD controllers

- EZ-PD™ CCG6 one-port USB-C & PD controller

- EZ-PD™ CCG6_CFP and EZ-PD™ CCG8_CFP Dual-Single-Port USB-C PD

- EZ-PD™ CCG6DF dual-port and CCG6SF single-port USB-C PD controllers

- EZ-PD™ CCG7D Automotive dual-port USB-C PD + DC-DC controller

- EZ-PD™ CCG7S Automotive single-port USB-C PD solution with a DC-DC controller + FETs

- EZ-PD™ CCG7SAF Automotive Single-port USB-C PD + DC-DC Controller + FETs

- EZ-PD™ CCG8 dual-single-port USB-C PD

- EZ-PD™ CMG1 USB-C EMCA controller

- EZ-PD™ CMG2 USB-C EMCA controller with EPR

- LATEST IN

- Aerospace and defense

- Automotive

- Consumer electronics

- Health and lifestyle

- Home appliances

- Industrial

- Information and Communication Technology

- Renewables

- Robotics

- Security solutions

- Smart home and building

- Solutions

- Overview

- Defense applications

- Space applications

- Overview

- ADAS & autonomous driving

- Automotive body electronics & power distribution

- Automotive LED lighting systems

- Chassis control & safety

- Electric vehicle drivetrain system

- EV thermal management system

- In-vehicle infotainment & HMI

- Light electric vehicle solutions

- Overview

- Power adapters and chargers

- Complete system solutions for smart TVs

- Mobile device and smartphone solutions

- Multicopters and drones

- Power tools

- Semiconductor solutions for home entertainment applications

- Smart conference systems

- Overview

- Power adapters and chargers

- Asset Tracking

- Battery formation and testing

- Electric forklifts

- Battery energy storage (BESS)

- EV charging

- High voltage solid-state power distribution

- Industrial automation

- Industrial motor drives and controls

- Industrial robots system solutions for Industry 4.0

- LED lighting system design

- Light electric vehicle solutions

- Power tools

- Power transmission and distribution

- Traction

- Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS)

- Overview

- Data center and AI data center solutions

- Edge computing

- Machine Learning Edge AI

- Telecommunications infrastructure

- Overview

- Battery formation and testing

- EV charging

- Hydrogen

- Photovoltaic

- Wind power

- Solid-state circuit breaker (SSCB)

- Battery energy storage (BESS)

- Overview

- Device authentication and brand protection

- Embedded security for the Internet of Things (IoT)

- eSIM applications

- Government identification

- Mobile security

- Payment solutions

- Access control and ticketing

- Overview

- Domestic robots

- Heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC)

- Home and building automation

- PC accessories

- Semiconductor solutions for home entertainment applications

- Overview

- Battery management systems (BMS)

- Connectivity

- Human Machine Interface

- Machine Learning Edge AI

- Motor control

- Power conversion

- Security

- Sensor solutions

- System diagnostics and analytics

- Overview

- Automotive auxiliary systems

- Automotive gateway

- Automotive power distribution

- Body control modules (BCM)

- Comfort & convenience electronics

- Zonal DC-DC converter 48 V-12 V

- Zone control unit

- Overview

- Automotive animated LED lighting system

- Automotive LED front single light functions

- Automotive LED rear single light functions

- Full LED headlight system - multi-channel LED driver

- LED drivers (electric two- & three-wheelers)

- LED pixel light controller - supply & communication

- Static interior ambient LED light

- Overview

- Active suspension control

- Automotive braking solutions

- Automotive steering solutions

- Chassis domain control

- Overview

-

Automotive BMS

- Overview

- Automotive battery cell monitoring & balancing

- Automotive battery control unit (BCU)

- Automotive battery isolated communication

- Automotive battery management system (BMS) - 12 V to 24 V

- Automotive battery management system (BMS) - 48 V

- Automotive battery management system (BMS) - high-voltage

- Automotive battery pack monitoring

- Automotive battery passport & event logging

- Automotive battery protection & disconnection

- Automotive current sensing & coulomb counting

- BMS (electric two- & three-wheelers)

- EV charging

- EV inverters

- EV power conversion & OBC

- FCEV powertrain system

- Overview

- Audio amplifier solutions

- Complete system solutions for smart TVs

- Distribution audio amplifier unit solutions

- Home theater installation speaker system solutions

- Party speaker solutions

- PoE audio amplifier unit solutions

- Portable speaker solutions

- Powered active speaker systems

- Remote control

- Smart speaker designs

- Soundbar solutions

- Overview

- Data center and AI data center solutions

- Digital input/output (I/O) modules

- DIN rail power supply solutions

- Home and building automation

- Industrial HMI Monitors and Panels

- Industrial motor drives and controls

- Industrial PC

- Industrial robots system solutions for Industry 4.0

- Machine vision

- Mobile robots (AGV, AMR)

- Programmable logic controller (PLC)

- Solid-state circuit breaker (SSCB)

- Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS)

- Overview

- AC-DC power conversion for telecommunications infrastructure

- DC-DC power conversion for telecommunications infrastructure

- FPGA in wired and wireless telecommunications applications

- Power system reliability modeling

- RF front end components for telecommunications infrastructure

- Satellite communications

- Overview

-

AC-DC power conversion

- Overview

- AC-DC auxiliary power supplies

- AC-DC power conversion for telecommunications infrastructure

- Power adapters and chargers

- LED lighting system design

- Complete system solutions for smart TVs

- Desktop power supplies

- EV charging

- Industrial power supplies

- Home and building automation

- Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS)

- Server power supply units (PSU)

- DC-DC power conversion

- Overview

- Power supply health monitoring

- LATEST IN

- Digital documentation

- Evaluation boards

- Finder & selection tools

- Platforms

- Services

- Simulation & Modeling

- Software

- Tools

- Partners

- Infineon for Makers

- University Alliance Program

- Overview

- Bipolar Discs Finder

- Bipolar Module Finder

- Connected Secure Systems Finder

- Diode Rectifier Finder

- ESD Protection Finder

- Evaluation Board Finder

- Gate Driver Finder

- IGBT Discrete Finder

- IGBT Module Finder

- IPM Finder

- Microcontroller Finder

- MOSFET Finder

- PMIC Finder

- Product Finder

- PSOC™ and FMx MCU Board & Kit Finder

- Radar Finder

- Reference Design Finder

- Simulation Model Finder

- Smart Power Switch Finder

- Transceiver Finder

- Voltage Regulator Finder

- Wireless Connectivity Board & Kit Finder

- Overview

- AIROC™ software & tools

- AURIX™ software & tools

- DRIVECORE for automotive software development

- iMOTION™ software & tools

- Infineon Smart Power Switches & Gate Driver Tool Suite

- MOTIX™ software & tools

- OPTIGA™ software & tools

- PSOC™ software & tools

- TRAVEO™ software & tools

- XENSIV™ software & tools

- XMC™ software & tools

- Overview

- IPOSIM Online Power Simulation Platform

- CoolGaN™ Simulation Tool (PLECS)

- HiRel Fit Rate Tool

- IPOSIM Online Power Simulation Platform

- Infineon Designer

- Interactive product sheet

- IPOSIM Online Power Simulation Platform

- InfineonSpice Offline Simulation Tool

- OPTIREG™ automotive power supply ICs Simulation Tool (PLECS)

- Power MOSFET Simulation Models

- PowerEsim Switch Mode Power Supply Design Tool

- Solution Finder

- XENSIV™ Magnetic Sensor Simulation Tool

- Overview

- AURIX™ certifications

- AURIX™ development tools

-

AURIX™ Embedded Software

- Overview

- AURIX™ Applications software

- AURIX™ Artificial Intelligence

- AURIX™ Gateway

- AURIX™ iLLD Drivers

- Infineon safety

- AURIX™ Security

- AURIX™ TC3xx Motor Control Application Kit

- AURIX™ TC4x SW application architecture

- Infineon AUTOSAR

- Communication and Connectivity

- Middleware

- Non AUTOSAR OS/RTOS

- OTA

- AURIX™ Microcontroller Kits

- Overview

- TRAVEO™ Development Tools

- TRAVEO™ Embedded Software

- Overview

- XENSIV™ Development Tools

- XENSIV™ Embedded Software

- XENSIV™ evaluation boards

- Overview

- CAPSENSE™ Controllers Code Examples

- Memories for Embedded Systems Code Examples

- PSOC™ 1 Code Examples for PSOC™ Designer

- PSOC™ 3 Code Examples for PSOC™ Creator

- PSOC™ 3/4/5 Code Examples

- PSOC™ 4 Code Examples for PSOC™ Creator

- PSOC™ 6 Code Examples for PSOC™ Creator

- PSOC™ 63 Code Examples

- USB Controllers Code Examples

- Overview

- DEEPCRAFT™ AI Hub

- DEEPCRAFT™ Audio Enhancement

- DEEPCRAFT™ Model Converter

-

DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Models

- Overview

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Baby Cry Detection

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Cough Detection

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Direction of Arrival (Sound)

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Factory Alarm Detection

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Fall Detection

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Gesture Classification

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Siren Detection

- DEEPCRAFT™ Ready Model for Snore Detection

- DEEPCRAFT™ Studio

- DEEPCRAFT™ Voice Assistant

- Overview

- AIROC™ Wi-Fi & Bluetooth EZ-Serial Module Firmware Platform

- AIROC™ Wi-Fi & Bluetooth Linux and Android Drivers

- emWin Graphics Library and GUI for PSOC™

- Infineon Complex Device Driver for Battery Management Systems

- Memory Solutions Hub

- PSOC™ 6 Peripheral Driver Library (PDL) for PSOC™ Creator

- USB Controllers EZ-USB™ GX3 Software and Drivers

- Overview

- CAPSENSE™ Controllers Configuration Tools EZ-Click

- DC-DC Integrated POL Voltage Regulators Configuration Tool – PowIRCenter

- EZ-USB™ SX3 Configuration Utility

- FM+ Configuration Tools

- FMx Configuration Tools

- Tranceiver IC Configuration Tool

- USB EZ-PD™ Configuration Utility

- USB EZ-PD™ Dock Configuration Utility

- USB EZ-USB™ HX3C Blaster Plus Configuration Utility

- USB UART Config Utility

- XENSIV™ Tire Pressure Sensor Programming

- Overview

- EZ-PD™ CCGx Dock Software Development Kit

-

FMx Softune IDE

- Overview

- RealOS™ Real-Time Operating System

- Softune IDE Language tools

- Softune Workbench

- Tool Lineup for F2MC-16 Family SOFTUNE V3

- Tool Lineup for F2MC-8FX Family SOFTUNE V3

- Tool Lineup for FR Family SOFTUNE V6

- Virtual Starter Kit

- Windows 10 operation of released SOFTUNE product

- Windows 7 operation of released SOFTUNE product

- Windows 8 operation of released SOFTUNE product

- ModusToolbox™ Software

- PSOC™ Creator Software

- Radar Development Kit

- RUST

- USB Controllers SDK

- Wireless Connectivity Bluetooth Mesh Helper Applications

- XMC™ DAVE™ Software

- Overview

- AIROC™ Bluetooth® Connect App Archive

- Cypress™ Programmer Archive

- EZ-PD™ CCGx Power Software Development Kit Archive

- ModusToolbox™ Software Archive

- PSOC™ Creator Archive

- PSOC™ Designer Archive

- PSOC™ Programmer Archive

- USB EZ-PD™ Configuration Utility Archives

- USB EZ-PD™ Host SDK Archives

- USB EZ-USB™ FX3 Archive

- USB EZ-USB™ HX3PD Configuration Utility Archive

- WICED™ Smart SDK Archive

- WICED™ Studio Archive

- Overview

- Infineon Developer Center Launcher

- Infineon Register Viewer

- Pin and Code Wizard

- Timing Solutions

- Wireless Connectivity

- LATEST IN

- Support

- Training

- Developer Community

- News

Business & Financial Press

Mar 10, 2026

Business & Financial Press

Mar 09, 2026

Business & Financial Press

Mar 05, 2026

Business & Financial Press

Mar 04, 2026

- Company

- Our stories

- Events

- Press

- Investor

- Careers

- Quality

- Latest news

Business & Financial Press

Mar 10, 2026

Business & Financial Press

Mar 09, 2026

Business & Financial Press

Mar 05, 2026

Business & Financial Press

Mar 04, 2026

Ethernet Camera Bridge for Software-Defined Vehicles

Transforming the Automotive industry with Ethernet Camera Bridge technology

By Amir Bar-Niv, Ethernet Solutions, Infineon Technologies

Software-Defined Vehicles (SDVs) are reshaping the automotive industry, delivering safer, greener, and more engaging self-driving experiences. Ethernet-based in-vehicle networks (IVNs) provides the connectivity, security, scalability, and control SDVs require, enabling over-the-air (OTA) updates that continually enhance vehicle utility and the driving experience, while unlocking new, recurring revenue streams for OEMs.

Ethernet has evolved over decades to meet real-world networking demands, accumulating a rich set of standards and features that address performance, reliability, and security, ranging from precise time synchronization and deterministic scheduling to robust access control and encryption. As the automotive industry began adopting Ethernet around 2014, propelled by single-pair automotive Ethernet (e.g., 100BASE‑T1 and 1000BASE‑T1) that reduces cabling weight and cost while boosting bandwidth, it quickly became the dominant in-vehicle backbone for high-data-rate functions like ADAS, perception, and infotainment. Modern automotive Ethernet leverages Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN) to guarantee bounded latency, supports service-oriented communication and diagnostics, and integrates security mechanisms such as MACsec and 802.1X to help mitigate cyber threats and comply with emerging regulations.

When every in-vehicle device - processors, controllers, actuators as well as sensors and cameras - communicates over Ethernet, the core promise of the SDV is realized: the ability to reprogram the network and adjust its key characteristics for advanced applications. We call this “Ethernet End-to-End.”

Ethernet features enable four key attributes that are crucial for SDV: Flexibility, Scalability, Redundancy and Controllability.

- Flexibility: Ethernet provides the ability to change data flow in the network and share devices (like cameras and sensors) between domains, processors and other shared resources (e.g., storage).

- Scalability: This is related to both the software and hardware of the SDV. Software-driven feature updates often require reconfiguration in how data and control traffic are routed, which Ethernet switches can handle through simple configuration changes. Hardware can be also modified over time in the SDV, and in many cases, the network will often need adjustments to accommodate new link speeds and QoS requirements. These updates are straightforward with Ethernet-based architecture.

- Redundancy: To meet functional safety requirements, redundancy must cover both mission-critical processors and the data paths between devices to protect the network. Ethernet’s switching and multipath capabilities enable path diversity as well as load balancing across the IVN backbone, delivering this redundancy through standardized hardware and protocols.

- Controllability: Real-time diagnostics and link-level debugging enable continuous self-diagnosis and fault management - tracking channel quality, link margin/degradation, and EMC vulnerability - using Ethernet Operations, Administration, and Maintenance (OAM). With advanced AI/ML analytics, network health can be predicted more accurately, supporting higher safety goals and delivering significant economic benefits.

As noted above, realizing the full capability of in‑vehicle SDN requires most devices in the car to be connected over Ethernet. In today’s advanced vehicle architectures, the high‑speed backbone is already Ethernet, but camera interfaces largely remain proprietary, point‑to‑point (P2P) links based on Low‑Voltage Differential Signaling (LVDS) physical layer technology. The two most common ones are GMSL (ADI) and FPD-Link (TI). Newer solutions, such as MIPI A‑PHY and ASA, are being developed, attempting to replace LVDS, yet they still operate as point‑to‑point solutions.

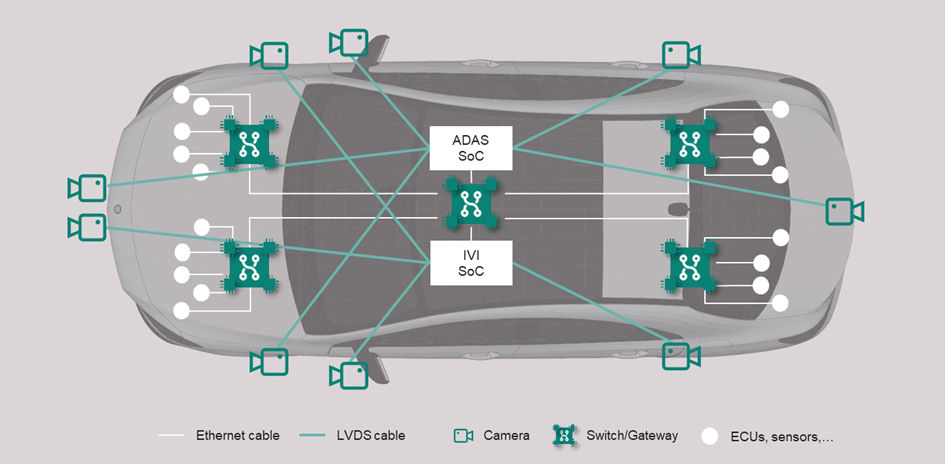

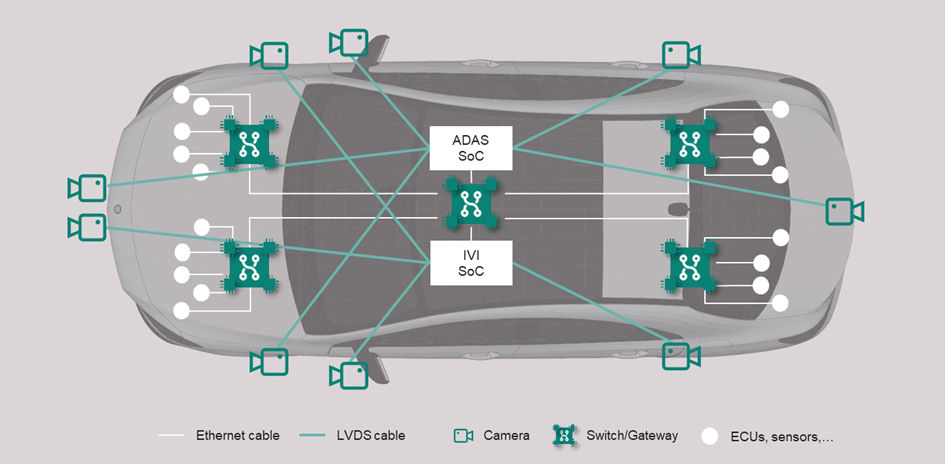

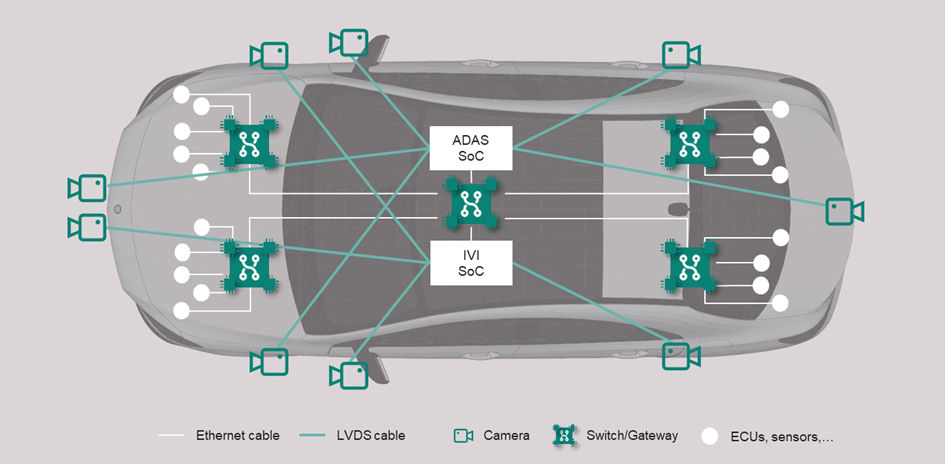

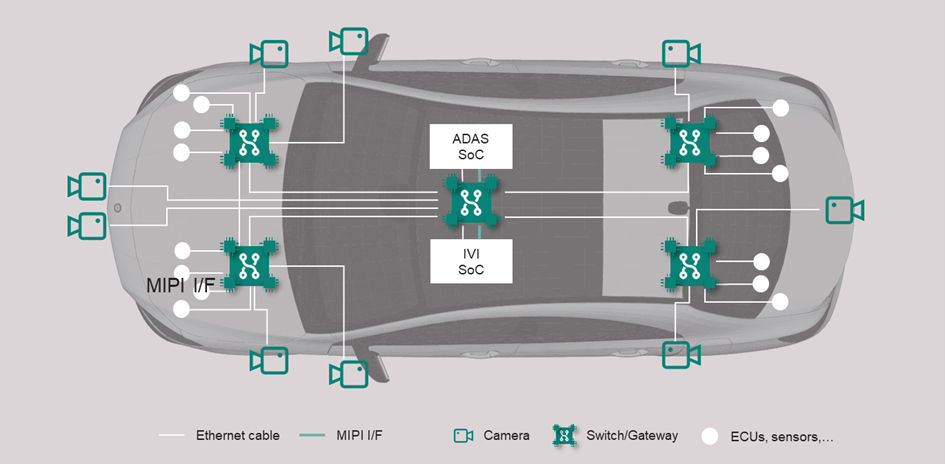

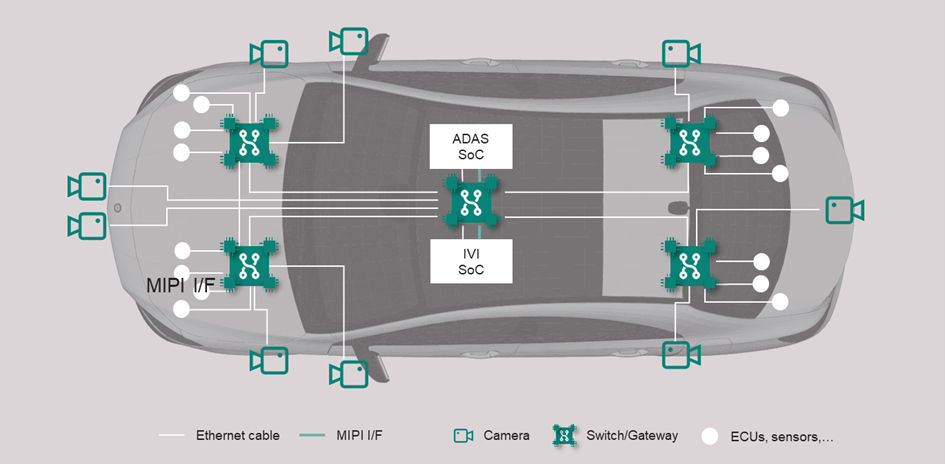

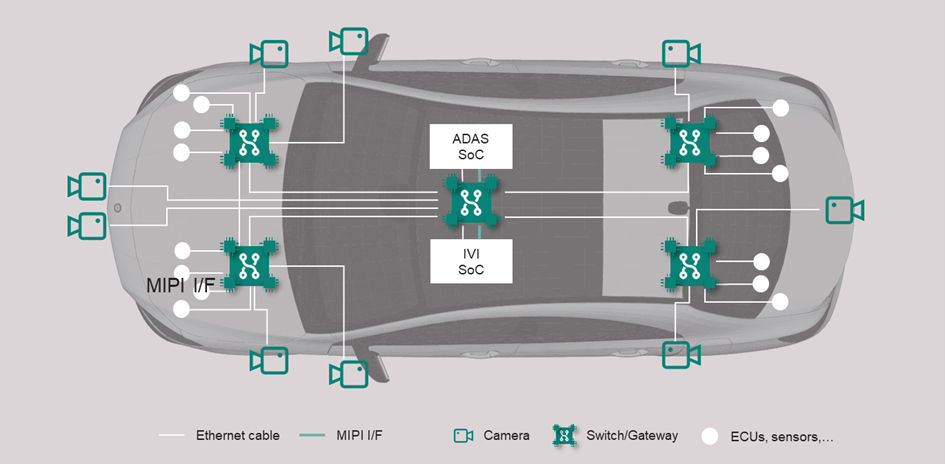

In Figure 1, we show an example of a typical zonal car network with the focus on the two domains that use camera sensors: ADAS and Infotainment (IVI).

In Figure 1, we show an example of a typical zonal car network with the focus on the two domains that use camera sensors: ADAS and Infotainment (IVI).

In Figure 1, we show an example of a typical zonal car network with the focus on the two domains that use camera sensors: ADAS and Infotainment (IVI).

As the diagram shows, most ECUs, sensors, and other devices (marked as small white circles) connect to - and benefit from - the zonal Ethernet backbone. However, cameras still use direct point-to-point links into the SoC devices, using long cables. These P2P connections make it difficult to share camera streams across ADAS and IVI domains. In addition, the topology lacks scalability, and redundancy is weak: because cameras are directly connected to one processor, a fault in that processor can sever access to those camera feeds.

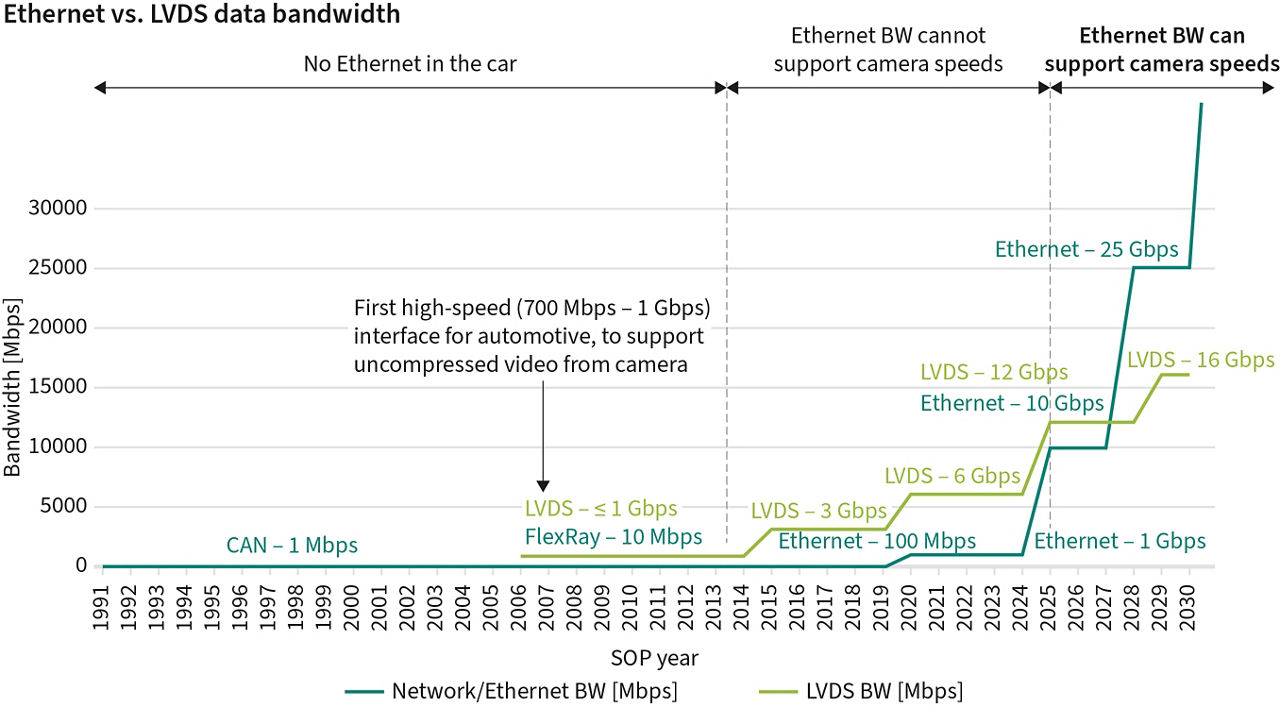

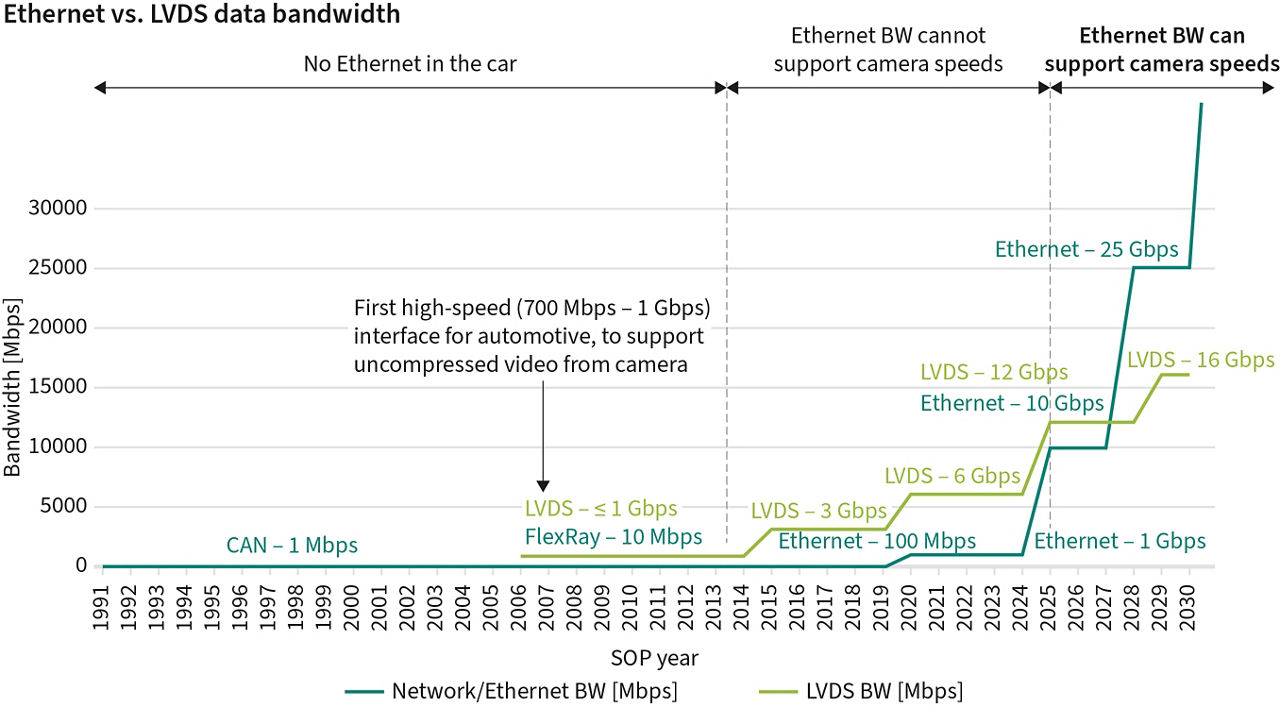

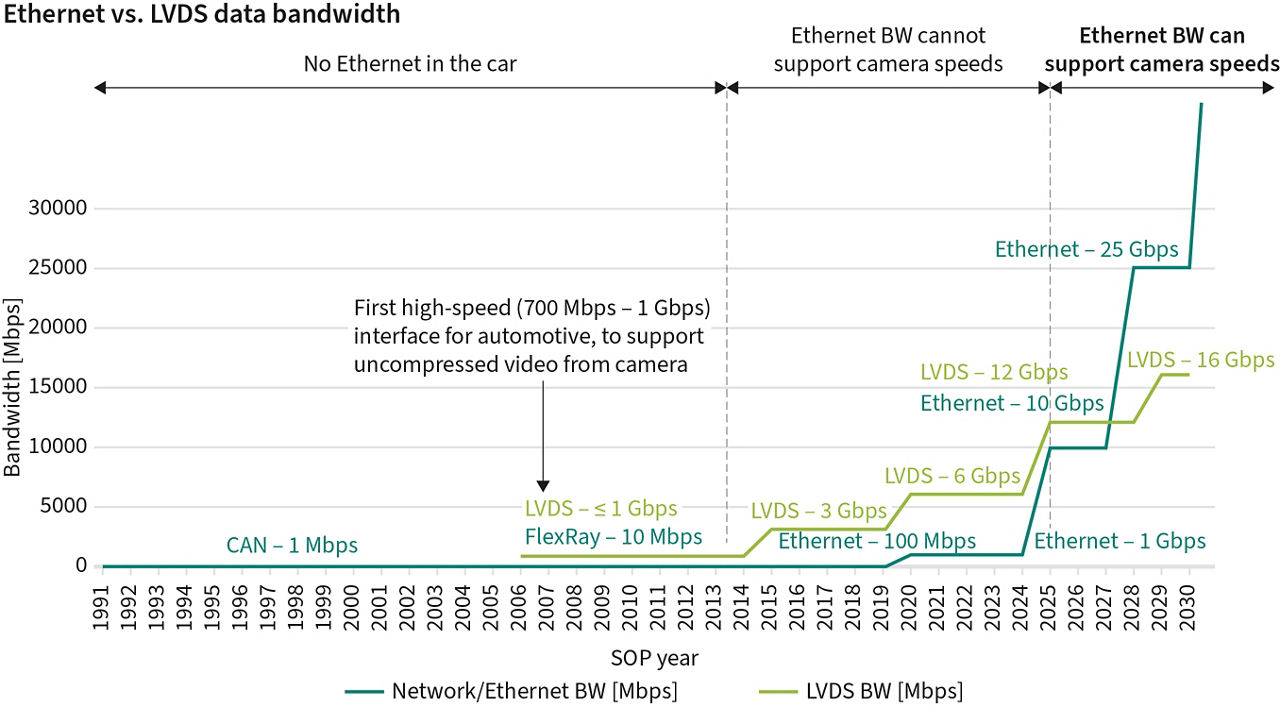

The best way to overcome the limitations of point‑to‑point (P2P) camera links is to convert the video to Ethernet right at the camera. Why wasn’t Ethernet used from the start? Historically, ADAS cameras avoid compression to minimize latency and preserve image quality, which pushes very high raw data rates. For many years, those camera rates exceeded what in‑vehicle Ethernet could deliver, as show in the figure below, so OEMs relied on proprietary serializers like GMSL and FPD‑Link (LVDS). While LVDS‑based links typically scaled by about 2× each generation, Ethernet tends to jump by an order of magnitude, and with the arrival of Multi‑Gig automotive Ethernet PHYs (2.5, 5, and 10Gbs), Ethernet finally caught up. Looking ahead, Ethernet is moving to even higher speeds - up to 25 Gbps - for next‑generation cameras.

With these Multi‑Gig PHYs, a new class of bridge devices can sit at the sensor, package the video using the IEEE 1722 audio/video standard, and carry it across the car’s Ethernet network with the right timing and quality.

IEEE 1722 is a standard for sending time-sensitive audio and video over Ethernet so streams arrive when and where they should.

How IEEE 1722 works in this context:

- For video, the camera bridge acts as an AVTP “talker,” and the ADAS or IVI SoCs are “listeners.” AVTP (Audio Video Transport Protocol), defined by IEEE 1722, is a Layer 2 transport for time-sensitive audio/video streams that standardizes payload format and timing over Ethernet

- It segments each video frame into AVTP protocol data units carried in Ethernet frames, tagging them with a unique Stream ID and sequence numbers for identification and loss detection.

- Each packet includes a presentation timestamp locked to the car’s clock (based on gPTP/IEEE 802.1AS), ensuring bounded latency and synchronized data with other sensors (radar, lidar, etc.) for accurate sensor fusion - critical for driver assistance.

- QoS is applied via VLAN priority and Stream, optionally with TSN shaping/scheduling (e.g., 802.1Qav/Qbv) so video gets guaranteed bandwidth and priority.

- Streams can be multicast to a group MAC address and, optionally using VLAN IDs, allowing multiple processors to subscribe to the same camera video without duplicating it at the source.

- For safety, resilience features like redundant paths and Frame Replication and Elimination for Reliability (IEEE 802.1CB) keep video flowing if a link or switch fails.

In addition, IEEE 1722 supports Controls and GPIO signals from the SoC to the camera:

- Using IEEE 1722.1, the computer discovers the camera bridge, reads its descriptors, establishes connections, and sends control commands (start/stop, exposure, gain, mode changes) alongside the video stream.

- GPIO is mapped to control/event messages. Inputs and outputs can be time-stamped to the gPTP clock for precise, synchronized triggers across multiple cameras.

- Control traffic is prioritized (and can use redundant paths/802.1CB) to ensure low-latency, reliable delivery even under load.

In short, IEEE 1722 lets camera video move across the car’s Ethernet network with the right timing, priority, and reliability, while IEEE 1722.1 provides simple, synchronized control and GPIO, enabling sharing across domains and robust redundancy. IEEE 1722 also includes provisions for radar-over-Ethernet, including support for SPI-based radar control.

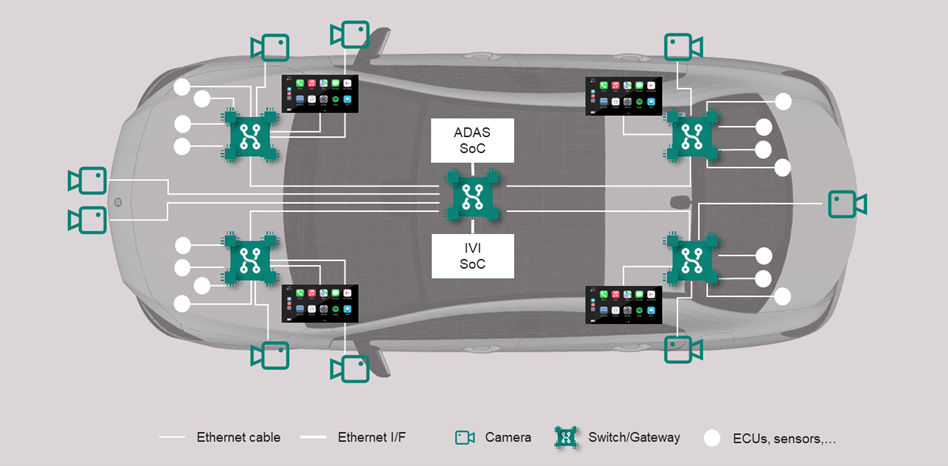

As illustrated below, once camera or radar outputs are converted to Ethernet, they can connect to central switches or dedicated Ethernet aggregators, allowing streams to be shared across multiple SoCs. When it’s cost-effective, cameras and radars can instead be attached to zonal switches using short, lightweight cables.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. Once the underlying technology for the camera interface is Ethernet, these links automatically gain access to all the other IEEE Ethernet standards, like:

- Switching and virtualization - IEEE 802.1

- Security – authentication and encryption – IEEE 802.1AE MACsec

- Time-Synchronization over network – IEEE PTP 1588

- Power over cable – IEEE PoDL 802.3bu

- Audio/Video Bridging – IEEE 802.1 AVB/TSN

- Asymmetrical transmission, using Energy Efficient Ethernet protocol – IEEE 802.3az

- Support for all topologies: Mesh, star, ring, daisy-chain, point-to-point

In addition, when a camera outputs Ethernet, the camera vendor can leverage the existing Ethernet test infrastructure/houses – covering compliance, interoperability, EMC, and more – that has been proven and accepted by the automotive industry for many years.

The next phase of Ethernet in the car, as shown in the next figure, is to bring all high-data-rate devices onto the network, including displays and central high-end compute units (SoCs). Future vehicles are expected to host two to five high‑resolution displays, which today often use proprietary point‑to‑point links such as LVDS. Migrating these displays to Ethernet allows them to benefit from the Ethernet capabilities discussed above (deterministic timing, QoS, security, diagnostics, and more) while reducing cost through a standards‑based, multi‑vendor ecosystem.

A parallel trend accelerating Ethernet end‑to‑end is the emergence of SoCs with native, high‑speed Ethernet ports, scaling up to 25 Gbps, plus dedicated hardware engines to depacketize IEEE 1722 video streams. This offloads the CPU, lowers latency, and enables seamless, scalable media transport over the in-vehicle network.

Replacing MIPI CSI-2 with native 25G Ethernet ports on the SoC delivers several concrete advantages for performance, architecture, security, and scalability:

- Consolidated bandwidth and fewer pins: A single 25G Ethernet port can aggregate multiple camera and radar streams, reducing high-speed lanes/pins, simplifying PCB/package, and eliminating external serializers over long reaches.

- Shareable and scalable: Ethernet enables multicast so ADAS, IVI, and logging can use the same stream; adding or re‑routing cameras becomes a software task, not a board redesign.

- Deterministic and low-overhead: gPTP/TSN provide tight timing. Hardware-based IEEE 1722 depacketization with DMA to ISP/GPU offloads the CPU and cuts latency.

Net result: Native 25G Ethernet makes the SoC a high-throughput, time-synchronized node in a programmable network, cutting pin count and PCB complexity while improving performance, resilience, and ease of adding and updating features over the vehicle’s lifetime.

Early multi-gigabit camera-to-Ethernet bridges used the symmetric single-pair PHYs defined in IEEE 802.3ch (e.g., 2.5/5/10GBASE‑T1). However, camera links are inherently asymmetric - high-rate video flowing from the camera to the SoC, with only low-rate control traffic in the reverse direction. To better match this traffic pattern and reduce PHY size and power, a new standard, IEEE 802.3dm, introduces asymmetrical single-pair Ethernet PHYs tailored for camera applications.

IEEE 802.3dm focuses on bringing asymmetric single‑pair Ethernet PHYs to automotive, tailored for links where traffic predominantly flows in one direction -such as cameras and displays. 802.3dm targets higher downstream data rates from the sensor to the processor (in the case of camera), paired with a lower upstream rate for control and status. The goal is to deliver the bandwidth needed for high‑resolution, low‑latency video while cutting PHY power, silicon area, and cost by not over‑provisioning the return path.

Technically, 802.3dm builds on the existing 802.3 automotive and adapts it for asymmetric operation over a single balanced pair. It aims to preserve the behaviors system designers rely on: full‑duplex operation, automotive‑grade EMC robustness, deterministic latency compatible with TSN at Layer 2, and optional features such as Power over Data Line (PoDL). It also targets typical automotive reaches and harnesses of 15m, supporting both STP and coax cables. By matching link rates to actual traffic patterns, 802.3dm helps save power at the edge, simplifies thermal design, and enables smaller camera modules without sacrificing image quality or timing.

From a system perspective, standardizing asymmetric PHYs enables true Ethernet end‑to‑end architectures for vision: cameras and displays can plug into zonal or central switches, share streams with multiple ECUs, and take advantage of the broader Ethernet ecosystem (TSN for scheduling, MACsec for security, PTP for time sync, PoDL or power-over coax (PoC) for power). This reduces the need for proprietary serializers, lightens wiring, and fosters a multi‑vendor supply chain.

Current status: 802.3dm is an active IEEE 802.3 project under development, with objectives that include downstream speeds of 2.5G, 5G and 10Gbps, and upstream of 100Mbps. The task force is refining technical parameters and draft text through the normal IEEE process (proposal evaluation, draft creation, and balloting). Draft 2.0 and starting the ballot phase is planned for May 2026.

Converting camera links to Ethernet at the edge unlocks Ethernet End-to-End for SDVs: video and control are encapsulated with IEEE 1722/1722.1, making streams shareable across ADAS and IVI, precisely time-aligned via gPTP/TSN, secured with MACsec, and observable with mature OAM, while benefiting from established automotive Ethernet compliance and EMC test ecosystems. As native 10–25 Gbps Ethernet and IEEE 1722 offload become standard in SoCs, the network delivers simpler scaling through software rather than rewiring. The emergence of asymmetric single‑pair PHYs in IEEE 802.3dm further optimizes camera links for power, size, and cost by matching high downstream video with lightweight upstream control. Together, these advances replace proprietary point‑to‑point chains with a programmable, resilient, and standards‑based fabric - reducing wiring and BOM, boosting reliability and safety, and accelerating OTA feature delivery throughout the vehicle’s life.